Hostage-Taking Using the Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling is used to take the country hostage demanding spending cuts as ransom. Cutting through the noise, we discuss how it works and possible solutions.

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

A debt ceiling crisis will soon be upon us. Already, Treasury Secretary Yellin is resorting to extraordinary measures to keep paying the country’s bills. Some House Republicans are salivating at the chance to hold the country hostage to obtain ransom in the form of some sort of unstated and probably unknown spending reductions. Doing so plays well to the Republican base despite the high risk to the US and world economies, and to the country’s reputation as a functioning democracy.

There’s a lot of misleading media coverage about the situation, so I think it could be useful to talk about the facts, their implications, why everyone should care, and what win-win solutions there might be.

What is the Debt Ceiling?

Origins

Back in 1917, the US was fixing to get into the war to end all wars. The US needed to issue bonds to finance that. Some members of Congress didn’t want to issue bonds. Some members didn’t want to get into the war.

So, a compromise was struck: OK, issue some bonds, but in exchange you must limit the total amount of debt in certain categories. Of course, the limits were too low and were quickly raised a few times.

Unfortunately, in 1939, it looked like the war to end all wars was just the precursor to another world war and Congress restructured the country’s debt to limit the nation’s aggregate debt — the debt limit or debt ceiling — without limits on particular categories of debt. The limit was raised in 1941 and every year thereafter until 1946, when it was lowered.

Since 1960, the limit has been lifted 78 times1. It has been a bipartisan affair, lifted 29 times under Democratic presidents and 49 times under Republican presidents.

Importantly, the debt ceiling is just a law passed by Congress. The Constitution and its amendments didn’t create it. Congress created it. Congress alters it. Congress could get rid of it.

Debt Ceiling Looks Backwards

Suppose I have a credit card with a $10,000 credit limit. When I charge a purchase to the card, the bank verifies that I haven’t exceeded that $10,000 limit before it approves the purchase. Once I get to the limit, the next time I try to make a purchase the bank says “no”. I can’t exceed the limit, even if my wife and I have promised each other that we’re going to take an expensive vacation.

That’s not how the national debt works.

When Congress passes a law that spends money (or, equivalently, reduces tax revenue), it often doesn’t know precisely how much it is spending. It simply promises to buy certain military hardware or subsidize renewable energy investments or lower certain taxes, or whatever.

Yes, it asks the Congressional Budget Office to estimate the cost, but the estimates are just that — estimates — which, despite the best efforts of some very smart people, are often wildly wrong because accurately predicting the future in a complex economy is impossible.

Likewise, Congress doesn’t accurately know how much tax revenue the government is going to collect because even without mucking about with the laws — which they do frequently — the revenue depends on many impossible-to-predict-accurately aspects of our complex economy.

So, Congress commits the country to spending unknowable amounts of money paid for by unknowable amounts of tax revenue. When the country spends more than it earns in tax revenue (and other stuff like fees and customs duties, but mostly tax revenue), the national debt goes up. There’s no bank to say “no” to Congress.

Instead, the US Treasury sells debt instruments (bonds, notes, etc.) to get the money to pay for the spending Congress has approved, increasing the country’s total debt. The Treasury constantly adjusts how much debt it issues to meet the country’s needs. Eventually, the national debt reaches the debt ceiling.

So what? Congress already committed the US to spend that money. People have been hired; contracts have been signed; individuals and companies have been promised benefits on which they depend; people, companies, and foreign governments have purchased prior debt instruments on which the US owes interest and return of principle at maturity; and much, much more.

These obligations don’t disappear when the debt ceiling is reached. The country still owes all of this money.

But the US Treasury can no longer sell debt instruments to borrow the money to pay for this spending that is already locked in.

It is in this sense that the debt ceiling looks backwards — it prevents the US from meeting the obligations to which Congress previously committed.

The debt ceiling, in and of itself, does not control future spending or tax revenue.

The Debt Ceiling Horoscope

“The debt limit [aka debt ceiling] measures nothing coherent and has no relationship to any serious measure of the economic burden imposed by the nation’s debt. It has as much relevance to the nation’s objective economic health as today’s horoscope.” — Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute

Any useful measure of the nation’s debt would be expressed relative to the size of our economy. Consider, for example, that the US debt at the end of World War II (1946) was $269B and the debt at the end of 2022 was $30,824B2. Just comparing debt levels would make you think that our debt is about 115 times larger now than then.

This is absurd because inflation has changed the value of the dollar and our economy today is much larger now than then. A more sensible measure is the ratio of debt to GDP, which, for 1946, was 119% and, for 2022, was 123%. So, in reality we have similar levels of debt then and now.

The debt ceiling also fails to capture accurately the cost of servicing our debt, that is, of paying the interest on the debt. Bivens gives the example that in 1996 federal debt was $5.2 trillion, costing 3% of GDP in interest payments, whereas in 2019 the debt was $22.7 trillion costing just 1.8% of GDP in interest payments. Why? Because interest rates collapsed as our economy weakened.

“[T]he larger point is that the level of gross federal debt has no reliable relationship to any economic stressor faced by governments or households, so hinging something as high stakes as a hard limit on the federal government’s legal ability to borrow on this measure makes no sense.” — Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute

Why Do We Still Have the Debt Ceiling?

We’ve seen that the debt ceiling is an arbitrary number cooked up by politicians, which bears no relation to any useful economic measure. It is backwards looking — it has nothing to do with controlling future spending, only about paying the money we already owe.

So, why do we still have it? The debt ceiling is politically useful for two purposes.

Virtue signaling

Politicians who want to virtue signal3 their fiscal responsibility to voters falsely conflate holding the line on the debt ceiling with reducing spending. Many voters seem to buy it.

Hostage taking

Defaulting on the country’s debt, which would happen if the debt ceiling isn’t raised, would have dire consequences harming the country, many individuals, and other countries. Everyone understands this, making the debt ceiling perfect for holding the country hostage.

Thus saith the hostage-taker: Pay the ransom or I’ll freeze the debt ceiling and blame you for the dire consequences. The ransom demanded could be anything, but typically is the imposition of austerity.

Take the example of the 2011 debt ceiling fight, during which Republican legislators refused to vote for raising the debt ceiling unless President Obama and Democrats in Congress agreed to large and immediate spending cuts.

President Obama blinked. He agreed to the Budget Control Act of 2011, which, through complicated mechanisms, forced significant budget cuts, reducing federal spending more than twice as much as the stimulus package of 2009 added to federal spending. This austerity program, implemented as we were working our way out of the Great Recession, led to the slowest recovery from recession in our history.

Once you show a hostage-taker that you’ll negotiate, the hostage-taker learns the lesson that taking hostages works to gain leverage.

Eliminating the Hostage-Taking Potential of the Debt Ceiling

Beyond virtue signaling, the debt ceiling is just a mechanism for hostage taking. In a sensible world, it would have long ago been repealed. But that’s not the world we live in and repeal of the debt ceiling seems unlikely anytime soon.

Several proposals have been made to neuter the debt ceiling. I consider all of these gimmicks, unworthy of a nation with a large, sophisticated economy. But they illustrate the absurdity of the the debt ceiling law, so I’ll outline them.

Gimmick #1: The Platinum Coin

The reason the government would default on our debts is that without selling more bonds there’s no way to deposit more money in the Treasury Department’s “checking account” held at the Federal Reserve Bank.

Not so, say promoters of Gimmick #1: The government has the authority to mint coins of any denomination any time. So, mint a one trillion dollar “platinum coin” and deposit it with the Federal Reserve Bank. Problem solved.

Gimmick #2: Premium Bonds

As my favorite finance columnist, Bloomberg’s Matt Levine, explains, the debt ceiling law caps the “face amount of obligations,” that is the principal that needs to be repaid at maturity. So, when the Treasury sells a $1,000 bond, $1,000 is added to the debt covered by the debt ceiling. When the bond matures, the government pays back that $1,000 in principal plus interest. For concreteness, let’s say that the interest rate is 5%. So, for a one-year bond, the government pays back $1,050.

But there’s no limit on the interest rate that the government can pay. Consider, then, selling a one-year $1,000 bond that pays 110% interest. When this bond matures, the government pays back the $1,000 principal plus $1,100 in interest, for a total of $2,100. An investor who expects to earn 5% interest would be happy to purchase this bond for $2,000 even though the face value is only $1,0004.

So, the debt capped by the debt ceiling goes up by $1,000 but the government actually gets $2,000 from the investor. This strategy could be deployed on a large scale to neuter the debt ceiling.

Gimmick #3: Ignore the Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling is a law. But the Constitution trumps (pun intended) laws and Section 4 of the 14th Amendment says

“The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

Seems pretty clear. Maybe the Treasury can just go ahead and issue more bonds to cover those unquestioned debts.

Of course, the attempted hostage-takers would likety-split have this before the Supreme Court, where who knows what would happen.

Would a Gimmick Help?

How would the world react if the Biden administration deployed any of these gimmicks? Nobody really knows. Just serious talk of deploying a gimmick could cause concern that could sink markets and, more importantly, call the “full faith and credit of the United States” into serious question around the world.

That said, it seems to me that the Treasury could experiment with all three gimmicks at some future time when there’s no impending debt ceiling crisis.

For example, start selling premium-priced bonds to gauge market reaction. If it goes poorly it would be easy to pull back, but if it goes well, the debt ceiling is neutered.

Similarly, the administration could bring the constitutionality of the debt ceiling in light of the 14th Amendment before the Supreme Court. If the Court rules the debt ceiling law unconstitutional, great, we’re done with this issue; if not, the situation is no worse than it is now, except perhaps for some political fallout about Democrats wanting to spend without limit.

Republicans Take Us Hostage

The mainstream media tends to portray the debt ceiling hostage situation with a large dose of bothsidesism. Here are two examples that Robert Reich gives:

The NY Times said “Members of both parties are intent on painting the opposition as culpable for the turmoil that would result from a catastrophic default on the debt this summer…”

CNN Anchor Erin Burnett has framed the fight as “a dangerous game of chicken,” in which “Republicans refuse to raise the debt ceiling without any strings attached,” while “the White House — well, they are going to the opposite extreme.”

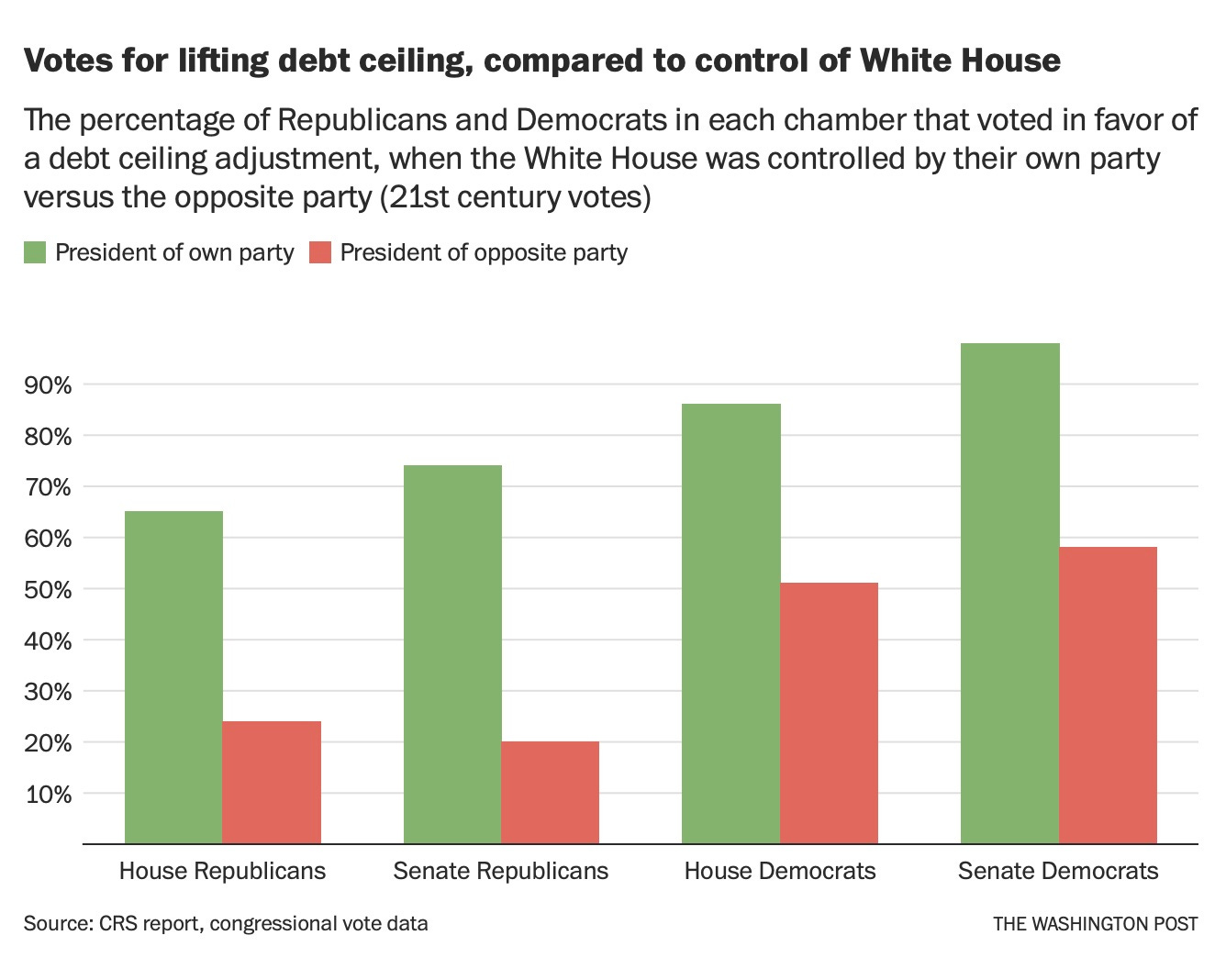

What’s the reality? The Washington Post analyzed 21st century votes to raise the debt ceiling and found that Republicans in both chambers of Congress vote to raise the debt ceiling in far greater numbers when there’s a Republican president than when there’s a Democratic president.

Democrats also exhibit this behavior, to a much smaller extent, not enough to hold the country hostage. Indeed, Democrats have never used the debt ceiling to take the country hostage during any administration in this century.

During the Trump administration, Republicans voted three times with little controversy to increase the debt ceiling, even as Trump’s tax cuts mushroomed the budget deficit making him among all presidents the proud purveyor of the third-largest increase in the primary deficit5, behind Presidents G.W. Bush and Lincoln6.

For a telling of the virtue signaling and hostage taking by some of today’s key GOP players, see Amy Davidson Sorkin’s article The New G.O.P. Takes the Country Hostage with the Debt Ceiling in The New Yorker.

Catastrophic Impact of Default

If the current debt ceiling impasse is not resolved, there will be significant impact on the economy. Nobody knows what would happen if we defaulted on our debt obligations, even temporarily. We’ve seen brief shutdowns of the federal government, which certainly harms the individuals affected and increases overall costs, but defaulting on our debt instruments would be a new, troubling event.

Economists have predicted the impact of various default situations, but it is difficult to have confidence in predictions about an event we’ve never experienced. Nevertheless, all of the predictions I’ve read are catastrophic.

For example, using their macroeconomic model of the economy, Bloomberg Economics simulated the effects of a three-months-long hostage taking. They predict that, in one quarter, GDP would decline at a 15% annual rate, with a lingering effect for many quarters to come, and long-term increased borrowing costs would result as confidence in US treasuries declines. (For comparison, the GDP declined 5.1% during the Great Recession in 2007-2009.)

President Biden’s Approach

President Biden is, correctly in my opinion, refusing to negotiate with the Republican hostage takers, led by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. Here’s how the President’s readout of his meeting with Speaker McCarthy put it:

“President Biden made clear that, as every other leader in both parties in Congress has affirmed, it is their shared duty not to allow an unprecedented and economically catastrophic default. The United States Constitution is explicit about this obligation, and the American people expect Congress to meet it in the same way all of his predecessors have. It is not negotiable or conditional.”

On the other hand, Speaker McCarthy told NPR:

"I want to look the president in the eye and tell me there's not $1 of wasteful spending and government. Who believes that? The American public doesn't believe that. Our whole government is designed to have compromise. For the president to say he wouldn't even negotiate, that's irresponsible."

Speaker McCarthy is posturing about budget negotiations, falsely conflating them with the debt ceiling.

A Win-Win Solution

The conflict over the debt ceiling seems intractable. The debt ceiling, originally intended in 1917 to make issuing debt easier, has been weaponized as a mechanism for taking the country hostage until some desired ransom is paid. A clean repeal of the law would be best, but isn’t going to happen anytime soon.

But there’s another approach that could be a huge step forward.

The McConnell Plan

In 2011, to help resolve that year’s debt ceiling standoff, Senate Minority leader Mitch McConnell introduced what came to be called the McConnell plan. It worked like this:

President Obama could raise the debt ceiling by as much as $2.5 trillion in three installments.

The President would have to submit each request to Congress, which would have 15 days to pass a resolution of disapproval. The requests would have to include proposals for spending cuts in the same amounts. Importantly, there was no mechanism for enforcing those spending cuts.

The President could veto any resolution of disapproval, which, of course, Congress could override with a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, something unlikely to happen with the Democratic-controlled Senate.

These rules expired at the end of President Obama’s first term.

The McConnell plan was adopted as part of the resolution of the 2011 debt ceiling crisis.

Protect Our Credit Act of 2023

Senators Jeff Berkley and Tim Kaine, both Democrats, wrote this week in The Washington Post that they’ve introduced the Protect Our Credit Act of 2023 (POCA), which would reinstate the McConnell plan and make it permanent.

This is a brilliant move because it is a win-win for the politicians.

Let’s look at the motivations of the various politicians involved in the drama:

Republican debt hawks: These politicians purport to want to lower the country’s debt. But they’re disingenuous as shown when they voted three times during the Trump administration to raise the debt ceiling in response to the rising debt caused by the Trump tax cuts.

What they really want is to grandstand on the debt to show their voters that they are debt hawks. The POCA lets them do that. They can go around blaming the president for increasing the debt limit. They can say that they tried, but sorry, voters, those tax-and-spend liberals are up to no good again.Republican MAGA adherents: These politicians want to show that democratic government is a failure so that they can replace it with an authoritarian oligarchy. Using the debt ceiling to create a crisis fits their goals. POCA gets in their way, but there aren’t enough of them to override a presidential veto.

Democratic debt doves: These politicians believe that federal debt is not a serious problem and that we should spend more to deliver benefits to the people. To them, the debt ceiling stands in the way of what they want to achieve. POCA removes a roadblock for what they want to do.

Democratic moderates: These politicians have some concerns about federal debt but want to hash out debt issues as part of the budgeting process. POCA puts the federal debate where it belongs, in discussions of the budget, where future debt is determined.

Presidents: Most presidents don’t want to preside over a messy public hostage-taking. POCA gives them a tool to avoid it, even though it might cost being branded as a spendthrift.

Short of a clean repeal of the debt ceiling, POCA is a good win-win solution for the country.

Summary

Republican politicians are wielding the debt ceiling law to hold the country hostage. What’s the ransom being demanded? Not clear. Some want to force steep reductions in social programs like Social Security and Medicare7. Others seem eager to create chaos for their own purposes. Others just want to grandstand on the debt.

President Biden is, so far, standing firm that he will not negotiate with hostage takers over the debt ceiling. We don’t know what alternatives, if any, he’s holding in his back pocket. Would he consider deploying one or more of the “gimmicks”?

Meanwhile, two Democratic Senators have sponsored a bill to implement a decade-old mechanism cooked up by Senate Minority Leader McConnell that would allow a win-win for many politicians while sidestepping harmful Republican hostage-taking attempts. Fascinating and maybe promising.

What’s Next?

You might have noticed that the lead image to this article was generated by an AI from a simple text prompt. After decades of promises not delivered, it appears that so-called artificial intelligence is once again poised to have large impact on our economy and on our society.

I plan to start discussing issues related to that impact. I’m not yet certain that I’ll be able to do this on our usual first and third Saturday of the month schedule.

See Why we have a debt ceiling, and why this trip to the brink may be different by Ron Elving.

Data from US National Debt by Year.

Definition (Merriam-Webster): “the act or practice of conspicuously displaying one's awareness of and attentiveness to political issues, matters of social and racial justice, etc., especially instead of taking effective action”

This is not fantasy. Bond traders regularly purchase bonds at a premium, although typically not such a large premium. There are some minor details to be discussed, which you can read about in Levine’s article.

The primary deficit is the gap between the non-interest spending, which are beyond policymakers’ control, and revenues, normalized by GDP.

I recognize that some Republicans deny this. But, the numbers simply don’t work unless there are big cuts in these programs or in defense — which seems to be off the table for some reason — or reversal of the Trump tax cuts.

I don't know the answer for sure, but I'd guess that even though Democrats controlled both houses of Congress they wouldn't have been able to overcome the filibuster in the Senate. Maybe they could have used the budget reconciliation process, which avoids the filibuster, but then there would have been cries about taking action in a partisan way, not that should have stopped them imho.

There was a NY Times article on this issue in December, but it doesn't really give a definitive answer either. It is at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/09/us/politics/congress-debt-ceiling.html.

Thank you, Lee. I never understood the concept of the debt ceiling. I have a much better handle on it now.