Inequality and Growth

Inequality ramped up starting in the early 80's; GDP growth has dropped since then. Coincidence or cause?

Welcome Back to Win-Win Democracy

As we discussed last time, the skewed distribution of income and wealth in our economy leaves a large part of our population in difficult straits, with little realistic expectation of their children having a better life. Their anger and resentment makes them receptive to populist appeals by authoritarian leaders, which is a major threat to our democracy.

Many people use the term inequality to describe the situation. I dislike this term because it incorrectly implies that equality is the solution. But I’m going to follow the crowd and use the term. Also, for brevity, I’m going to say inequality but I specifically mean economic inequality.

This begs the question: What distribution of income and wealth would we desire and why? Currently, we are on a path to ever increasing inequality of both income and wealth? Should we take action to veer off that path? If so, why? And, how?

These are our topics for this and the next several issues of the newsletter.

Ethics in Economics

Writing in his book Ethics in Economics: An Introduction to Moral Frameworks Jonathan Wight says (p. 3):

“Economics is thought to rely on the hardheaded calculation of rational self-interest; ethics is often portrayed as mushy do-goodism. Is there any useful connection between these subjects? … In addition to concern for an efficient outcome, people are motivated by considerations of justice and principles of duty and virtue.”

Wight gives a compelling example of the issue at hand. In 1999, a jury awarded plaintiffs in a suit against General Motors $107.6M in compensatory damages and $4.8B in punitive damages as a result of a firey crash in which a drunk driver rear-ended a Chevy Malibu and the gas tank exploded. GM knew that the placement of the gas tank made the car prone to fire in rear-end collisions. And GM knew how to fix it.

Here was GM’s economic analysis: It would cost $8.59 per car to fix, but only $2.40 per car to settle product liability lawsuits based on an expected liability of $200,000 per life lost. Conclusion: don’t fix it.

One juror, however, told reporters, “We're just like numbers, I feel, to them. Statistics. That's something that is wrong.” The juror wished that GM had also considered right and wrong. The problem is that there’s no universal definition of right and wrong.

You could argue, for example, that GM made its decision based on ethical egoism — the idea that people and organizations are morally required to act in their own self interest.

Someone else might argue that customers should be able to choose between more safety at a higher price or accepting more personal risk in exchange for a lower price. This is a valid viewpoint too. (In this particular case, GM kept withheld information from customers, depriving them of the information needed to make such a decision.)

Ethical issues inform policy decisions and we’ll find it necessary to discuss ethical issues, but I want to start our discussion just focusing on the economic implications of inequality.

We’ll turn to the ethical issues in future issues of the newsletter.

How Does Inequality Affect Growth?

Many politicians (and their followers!) have strongly-held opinions about how inequality affects the economy.

Advocates of trickle-down economics — a view generally associated with Republicans since the Reagan revolution — say give more money to the rich (through tax breaks, subsidies, and bailouts) and they’ll use it to invest, innovate, and create jobs. Do that, they say, and the economy will grow, with the benefits trickling down to everyone else.

Others advocate wealth redistribution — a view generally associated with progressive Democrats like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — using government power to take money from the wealthy (often through targeted tax increases or closing loopholes) to help the poor and middle classes, and to improve infrastructure and educational opportunities. Do that, they say, and the economy will grow because the poor and middle class will have some money to spend, we’ll make public investments that will help future growth, and the wealthy will still have plenty.

How’s Our Growth?

We’re going to look at the arguments and the evidence, but first we need some context — how has the economy has been doing? There are many useful measures of economic health, but gross domestic product (GDP) is the one number most commonly used to assess whether the economy is growing or shrinking.

Let’s look at how GDP has grown and shrunk over about the last 75 years:

The light blue curve shows quarterly data over about the last 75 years. Each datum is the percentage change in GDP from the same quarter the previous year — in other words by what percentage has GDP grown or shrunk. There’s a lot of noise in such data so it is useful to look at a smoothed version: The dark blue curve shows the three-year moving average trendline.

We can see that during the 1960s and 1970s the growth rate was itself increasing. But something changed starting in the 1980s and the growth rate mostly declined until the lead-up to the great recession. The recovery coming out of the Great Recession was anemic with a low growth rate until the pandemic-induced sharp decline.

The GDP growth rate has been declining since the early 1980s, with an anemic recovery in growth after the Great Recession.

This is remarkable, given the huge infusions of money into the economy in the wake of the Great Recession:

The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) injected about a half trillion dollars.

Near-zero interest rates and quantitive easing (massive purchase of bonds by the Federal Reserve).

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA, aka Trump tax cuts) injected about one and a half trillion dollars in tax cuts.

Even with huge interventions, our economy is growing slowly.

Houston, we have a problem!

How’s Our Income Inequality?

Here’s a long-term view of income inequality in the US, as measured by the share of the national income taken by people in the top decile of income:

Observe how high it was during the period building up to the Great Depression, then it leveled off during the post-war period from the 1950s until the late 1970s, when it started its march to Depression-level heights in the 21st century.

The timing is striking: Our current inequality began its rapid rise in the late 1970s at the same time as our GDP growth began its fall.

Many people have observed that the downward trend in GDP growth coincides with our country’s increasing inequality. Coincidence or causation?

Modeling Growth and Inequality

The relationship between inequality and economic growth has been hotly debated, with some arguing that rising inequality fosters economic growth and others arguing that rising inequality retards growth.

Both viewpoints make some intuitive sense. An economy with everyone having the same income and wealth removes all incentive for hard work, innovation, education, and investment. An economy where a few people own the vast majority of wealth and income, with most people earning just enough to survive, also removes the incentive for hard work, education, innovation, and investment.

Neither works. Balance is needed.

Gini Index

Understanding how inequality might affect growth requires some way to measure inequality. The Gini index (also called the Gini coefficient or Gini ratio) is commonly used as a measure of the dispersion of income (or wealth) among a population. It is a number from zero — meaning perfect equality — to one — meaning one person has all of the income. Sometimes it is stated on a scale of 0 to 100. (If you’re at all into math, you might find the Wikipedia article interesting.)

As you’d expect, no single number can characterize something as complex as the distribution of wealth or income1. Nevertheless, it has been used by many researchers and policy analysts.

Worldwide

Here’s a view of the Gini index for countries around the world2. Darker shades indicate higher indices. (Note: the data are not all for the same year.)

The United States is an inequality leader among major economies.

United States Over Time

Here’s how the Gini index (scale of 0 to 1) has been changing in the United States since 1967, showing, as to be expected from the top decile income share growth we saw above, that we are increasing our inequality substantially.

Impact of Rising Inequality on Growth

The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) has studied the impact of income inequality on economic growth across the advanced economies in the OECD.

Their approach uses regression analysis (a statistical technique) to explore how well various measures of inequality predict GDP per capita growth over a five-year period, using real data from similar advanced economies around the world. The analysis was repeated with different measures of inequality to test their predictive power and to estimate the impact of changes in the measure.

The Gini index (0 to 100 scale) is one measure.

The impact is, as the OECD reports puts it, “sizable”: Reducing the Gini index by 1 translates into an increase in growth by .8% in the following 5 years.

Between 1985 and 2005, inequality increased by more than 2 Gini points on average across 19 OECD countries. The study estimates that this growth in inequality reduced cumulative growth by 4.7% in 1990-2010.

But, remember, the US is a leader in inequality growth: We increased by 5 Gini points, not 2, in that time period, reducing the cumulative growth in 1990-2010 by even more.

Another interesting result comes from replacing the Gini index with a measure of bottom inequality, the ratio of the average income in the country to the average income in one of the bottom four deciles, and, separately, with a measure of top inequality, the ratio of the average income in one of the top two deciles to average income in the country. The results show that reducing bottom inequality has a statistically significant positive impact on growth, but reducing top inequality does not.

Some Thoughts

An empirical model like this provides important evidence that inequality does indeed reduce growth. These are sophisticated analyses that incorporate important assumptions and simplifications, which makes it difficult for laypeople like me (and probably you) to be confident of the results.

Scanning the literature it is clear that producing such models has been a long-term effort in economics with a lot of debate about the merits of various approaches. This debate is ongoing.

Let’s also look at other approaches to thinking about inequality and growth.

You’re Paid What You’re Worth

A common refrain in discussions about wages is that you’re paid what you’re worth. If you were worth more to the business, or to society, you’d earn more.

Nobel laureate in economics, Joseph Stiglitz, explains3:

“[M]arginal productivity theory maintains that, due to competition, everyone participating in the production process earns a remuneration equal to her or his marginal productivity. This theory associates higher incomes with a greater contribution to society. This can justify, for instance, preferential tax treatment for the rich: by taxing high incomes we would deprive them of the ‘just deserts’ for their contribution to society, and, even more importantly, we would discourage them from expressing their talent. Moreover, the more they contribute— the harder they work and the more they save—the better it is for workers, whose wages will rise as a result.

The reason that these ideas justifying inequality have endured is that they have a grain of truth in them. Some of those who have made large amounts of money have contributed greatly to our society, and in some cases what they have appropriated for themselves is but a fraction of what they have contributed to society.”

But, he then goes on to say:

“[There are other possible causes of inequality. Disparity can result from exploitation, discrimination and exercise of monopoly power. Moreover, in general, inequality is heavily influenced by many institutional and political factors – industrial relations, labor market institutions, welfare and tax systems, for example – which can both work independently of productivity and affect productivity.

What are the “institutional and political factors”?

Rent-seeking

In economics, the term rent-seeking means seeking additional wealth without producing additional value. For example, a company might lobby the government to create regulations that limit competition. Doing so doesn’t produce any additional value for society but might allow the company to take a larger share of the wealth already being generated.

Executive earnings are another example of rent-seeking. The huge increases in executive compensation in the US far outpace corporate performance and are due mostly to poor corporate governance at the board level, which allows executives to more or less set their own compensation. In particular, corporate compensation is often based on stock performance, which depends on many factors that have nothing to do with executive performance.

Indeed, does anyone really believe that the 15-fold increase from 1965 to 2013 in the ratio of executive compensation to average worker compensation is because the relative productivity of executives to the average worker has increased 15-fold? No, it is because executives are earning rents.

This is particularly true of top earners (not just the senior executives) in the financial services industry, who have earned rents from the massive subsidies that taxpayers provide the industry. Banks that are “too big to fail” benefit from an implicit government guarantee. This is another form of rent-seeking. The near-zero interest rates the Federal Reserve has set since the Great Recession is a boon to financial services corporations. Yet more rent-seeking.

Rent-seeking delivers income and wealth to the top without creating new wealth in the economy. Where does that income and wealth come from?

Rent-seeking gives unearned income and wealth to the people at the top, taking it from the people at the bottom.

To make matters worse,

Our tax policy, which gives preferential treatment to capital gains, amplifies the benefits of rent-seeking to high earners.

Weakening of Workers’ Bargaining Power

Since the early 1980s, corporations have passed only a little of the benefit of increasing productivity to workers, primarily because worker’s bargaining power has decreased dramatically since then, some of it in response to both government actions and inactions. We’ve discussed this in a previous newsletter, so I won’t go into detail here.

But since we’re now experiencing high inflation, it is important to understand that when central banks raise interest rates to combat inflation they drive real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) wages down, further weaken workers’ bargaining power, and exacerbate the inequality that weakens growth.

Discrimination

Both income inequality and wealth inequality affect our economic growth. And, discrimination plays an important role in both. People who are forced to live in poor neighborhoods lose both the opportunity to build wealth through housing appreciation and the opportunity for their children to get good educations.

Wage discrimination by gender and race is well documented and remains persistent despite some progress. Jobs that were once “women’s jobs” — like teaching and nursing — are still underpaid compared to other jobs that require similar levels of training and education. Government agencies that fight discrimination are underfunded and enforcement is lax.

Discrimination remains a powerful force in our country’s economic life, which limits the ability for many of our people to be paid “what they are worth.”

Paid What You’re Worth is Wrong

The whole notion of being paid what you’re worth is predicated on competitive markets adjusting compensation to levels consistent with the value you add to the economy. We’ve seen, however, that this is not what happens in real life. Instead:

Through rent-seeking at the top and forces unrelated to competition that weaken worker’s bargaining power (e.g., weak enforcement of labor laws; tax system that encourages moving jobs overseas) and opportunities at the bottom, the theoretical competitive market that would adjust compensation to value added doesn’t exist.

Weak Demand

I have been an executive at three large American companies — IBM, Microsoft, and Hewlett-Packard. I have never heard a discussion along the lines of “money is cheap, so let’s do x” or “taxes are low now so let’s do x”. Every discussion I can remember about whether or not to make an investment starts with “are there customers who want x?,” or “are there potential customers we could get if we do x?,” or “can we sell more if we do x?”

Businesses decide whether or not to make investments based primarily on whether there is demand for a product or service. Sure, eventually executives look at the financial aspects of an investment, but it all starts with evidence (or hope) that there is demand, which then leads to growth.

Our economy is largely driven by consumer spending. Our consumer spending has been growing but the growth has slowed since the early 1980s:

This graph shows the percentage change in consumer spending year over year. The slowdown in the growth of consumer spending since the early 1980s is striking.

This could be because the economy was incapable of producing goods and services that consumers wanted to buy, or it could be because consumers didn’t have money to spend.

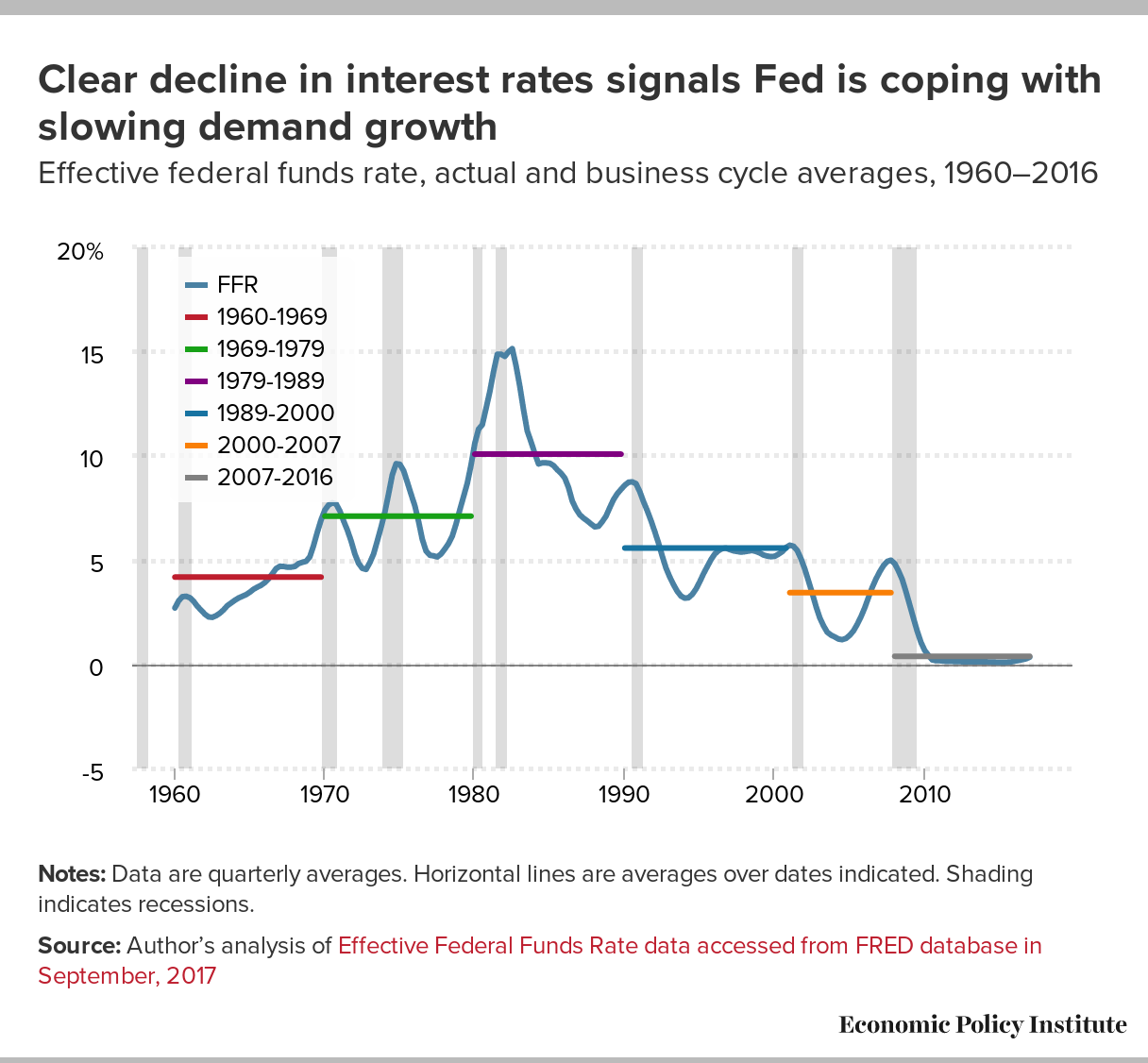

If it was the former, we would have seen inflationary price pressures. But we’ve had the opposite — the Federal Reserve drove interest rates down to near zero to encourage demand growth:

Indeed, growth in consumer demand has been slowing because so many consumers don’t have money to spend.

Why? Those at the bottom must spend a larger fraction of their income than those at the top. So, income and wealth delivered to those at the top results in far less consumer spending than the same aggregate income and wealth delivered to the much larger number of people in the bottom and middle.

Policies that encourage inequality discourage demand.

Much more detailed evidence of inequality’s impact on demand appears in the Economic Policy Institute’s report by economist Josh Bevins Inequality is slowing U.S. economic growth. It is worth noting that Bevins estimates that the drag on demand from the inequality increases starting in the early 1980s reached 4% of GDP by 2007 and continues to compound.

Impact on Future Growth

We’ve seen strong evidence that our increasing inequality has already substantially reduced the growth rate of our economy by lowering the growth of demand. This is despite the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing and low interest rates since the Great Recession, which have artificially propped up our economy for a decade.

Joseph Stiglitz argues that our high levels of inequality will further harm future growth through three additional mechanisms:

The millions of American children living in poverty face not only the lack of the educational opportunity to compete in our modern economy but also the lack of adequate nutrition and health care. Having so many children unlikely to be able live up to their potential will lower future growth.

Societies with great inequality are less likely to make public investments that enhance future productivity, such as transportation, infrastructure, technology, and education. Why? Because the rich, who have outsized political power, don’t think that they need these public investments.

Countries with high inequality have policies that encourage the financial sector over other activities that are more productive for the overall economy. In the US, for example, we give preferential tax treatment to the results of financial speculation (i.e., capital gains) and our tax laws encourage creating manufacturing jobs elsewhere.

Summary

Inequality in the United States has increased dramatically since the late 1970s. Almost in lockstep, growth has slowed too. There is considerable evidence that rising inequality causes slowing growth.

Even before considering the moral and ethical issues of inequality, we’ve seen that the trickle-down economics of the Reagan revolution have failed all but the wealthiest among us. Lower- and middle-income people are struggling as they get an ever-smaller share of an economy that is growing ever more slowly.

The idea that people get paid what they’re worth is wrong. Through mechanisms like rent-seeking, very high income people are being paid more than they would be “worth” in a truly competitive market. And, low-income people continue to be shortchanged by policies and practices that weaken workers’ bargaining power, so that they are paid less than what they would be “worth” in a truly competitive market.

What’s Next?

I’ve intentionally kept ethical and moral considerations out of today’s discussion. Next time I plan to introduce some of those considerations.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty explains it this way: “The statistical measures of income inequality that one finds in the writings of economists as well as in public debate are all too often synthetic indices, such as the Gini coefficient, which mix very different things, such as inequality with respect to labor and capital, so that it is impossible to distinguish clearly among the multiple dimensions of inequality and the various mechanisms at work.”

Comparisons like this are fraught because of variations in data quality, and in data collection and analysis methods.

A free pre-print is available on Stieglitz’s Columbia University web site at https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/Inequality%20and%20Economic%20Growth.pdf.

The US GDP is 70% consumer spending, and the rest about evenly divided by government, company internal investment in capital, and exports. The ultra rich, which are are tens of thousands of families, will be spending more, while the middle class and poor will be spending less, obviously changing the demand for for products. The poor will look for a smaller apartment for lower rent, and cut food costs, probably resulting in a less healthy eating and later medical problems. Buy companies that sell low cost food, with lots of sugar and carbs. The middle class will wait longer to buy a first house, and cut corners, and will spend less on leisure travel to accumulate the house down payment, and pay the mortgage. Sell short cruise lines, and the housing industry. The top end of the wealthy, like Paul Allen, will commission the building of half billion dollar yachts. Now that he he has died, is kids cannot affort the upkeep and sold it off to a company that how leases it, to the filthy rich, that cannot affort a half billion dollar yacht, but can afford to lease one for a month. It is hard to know what to invest in to take advantage of the greater spending power of these people. They own multiple luxury homes, dominating the corner condo market in tall buildings, selling for 8 figures, that are only used a few weeks a year, instead of a luxury hotel suite, and digital one of a kind art.

The marginal extra disposable income of the poor and middle class, often go toward saving for owning housing, or paying the mortgage on it, or educating their children. These two things increase the intellectual capital and housing stock, as well as the savings as cash help finance industrial growth a bit. Whether Paul Allen's yacht is in his hands used for a few weeks a year, or leased out to 12 people a month at a time, it is of no value to the economic activity. There is simply a one time diversion of materials and workers to building the yacht, that could have gone to building another 1000 average houses that year.

This shifting of purchasing basic essentials, housing, and low end leisure and entertainment for large markets, drives lots of innovation, to give effective products at an affordable price. This results in permanent additions to the intellectual capital, knowledge, patents that go beyond the semiconductor lines that cost billions. The yacht was probably filled with electronics, that only a major navy can afford or needs, but the yacht market is thin, and there is no incentive to develop better technology for building them.

I think it pretty clear that shifting income to the high end will shift consumer purchases in a way that will lower growth. Of course it would take lots of input numbers and a good model to really make the case.

Milton Friedman, the University of Chicago economist, for decades was selling the idea that the stock holder was the only stake holder, and should get the primary reward. It really took hold around the Reagan administration, where labor was weakened in other ways, lowering their income. The result was the Jack Welsh GE CEO, who returns all of the value of a large corporation, in the form of dividends and stock buybacks. It has impoverished innovative companies R&D, like GE (now going through liquidation), Kodak and Xerox through bankruptcy, and IBM and HP revenue declines. This is an economic religious philosophy that has both lowered productivity improvements directly and exacerbated income disparity.

Reagan, Friedman, and Welsh both put more income into the hands of the wealthy, but also sold off, or let their productive capacity rust away. They contributed to both slower growth and inequality at the same time.

I believe that the term "trickle down" goes back to an Eisenhower Cabinet member, and former GM executive, who said "what is good for GM is good for the country."

Finally, the discussion reminds me of a secton of Alexis de Tocqueville in his book Democracy in America. He talked about the effect of the difference in income in France, which he knew well, where the Aristocrats had all the spending power, and having more money than god, were insensitive to price, and the United States, where 200 years ago, the big market was farmers, and few people had a large fortune, and likely it was not that huge. (the largest clump of capital was actually the market value of the slaves, but he did not write about that.)

He said that in France, the wealthy could afford exquisitely perfect products from the artisans, where as in the USA "just good enough" was the sweet spot, where you could make good money with a large market. I recall his mentioning shovels., where there was no point in making it any nicer than meeting a farmers needs. The dies, forms, and skills to build a good shovel for manure represent an accumulation of capital within society, but making hand made beautiful shovels, do not.

All of these things suggest to me that the income shift upward is bad for economic growth.

Please consider the topic of "poverty traps" in future issues related to economic inequality. Poverty traps are real, and some could easily be eliminated. For example, even if just 1% of spending became part of an individual retirement plan, wealth creation would be greatly accelerated.

Also see https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220803-citizen-future-why-we-need-a-new-story-of-self-and-society